The 'Space-for-action Barrier' Trap And A Way To Move Forward

The thing that prevents you to do “what should be done”.

Hi everyone, Kevin here.

Some times ago, I proposed the concept of “space-for-action barrier” as a potentially useful description of the conditions of a context that hinders your ability to act & learn in a “necessary space” because of imposed constraints.

I recently wanted to extend it a bit further and provide a path through it, in the light of 1) some words of wisdom from D. Snowden and; 2) my own, surely limited, understanding of his work at Cognitive Edge and my endeavour through Systems & Complexity themes.

The “necessary space” here is what we think/believe we ought to do in order to understand the context and discover possibilities that could lead to novelty. In my article “The Multiples Design Thinking”, I describe the concept as such:

“Most of the time, when we work within companies or on specific projects, there is an assumed “space for action” on which either the project is based or the company expectations are built. This space for action is unconsciously determined by the type of outcomes, the “horizon” that a company is able to foresee [from its current context]. Narrow outcomes or not-so-far horizon means limited space for action.

These constraints […] are totally blind toward the complexity of the reality it evolves in! Unfortunately, their implications are huge.

The barrier happens when designers, innovators, or change agents try to redefine these constraints to make alignment with reality. Indeed, this barrier is the system’s immune response to change. As I said, this barrier impacts our ability to think, act, and therefore navigate: ignorance –or illusion of certainty– is sometimes preferable to some organizations.”

Now, I would probably talk of “system’s immune response to forced change” instead: complex systems, like organizations and the people that compose them, are not averse to change by definition, it’s quite the contrary, systems do change all the time but only when the context necessitates such adaptability.

In other words, this is a mismatch between “expectations” that emerges from the current ordered context (and therefore are bounded to initial conditions, the knowns) and “intentions” to reach a yet-to-be-discovered future state and explore the unknowns. This creates ambiguity.

An instinctive way to handle this is generally to devise an ideal future state, like “only when we’ll do X will we be innovative”, and work backward to devise a linear course of action to reach this state. One problem with this is that it tends to create a non-inclusive, binary (either/or), and reductive narratives that flattens the diversity of contexts and negates/dismisses any other possibilities: the kind of thinking that leads to extremes (polarization) when confronted with contradictions.

The kind of game played by consultancy firms & agencies because, let’s face it, reductive & simplistic narratives (supported by numbers) are easier to sell.

Another problem is that design and innovation are not linear. As Enrique MG explains in his article soberly titled ‘8 | Planning’:

“Planning is a linear process that moves in one direction, always forward.

Designing is multi dimensional and moves forward, backward, and sideways as needed.

Planning is scripted: a good plan leaves nothing to chance.

Designing is a dynamic process that adapts to its context in order to respond to uncertainty.

Planning [begins] with the desired solution and then goes backward to figure out the steps needed to get there.

Designing never starts with a solution: it starts with a question.”

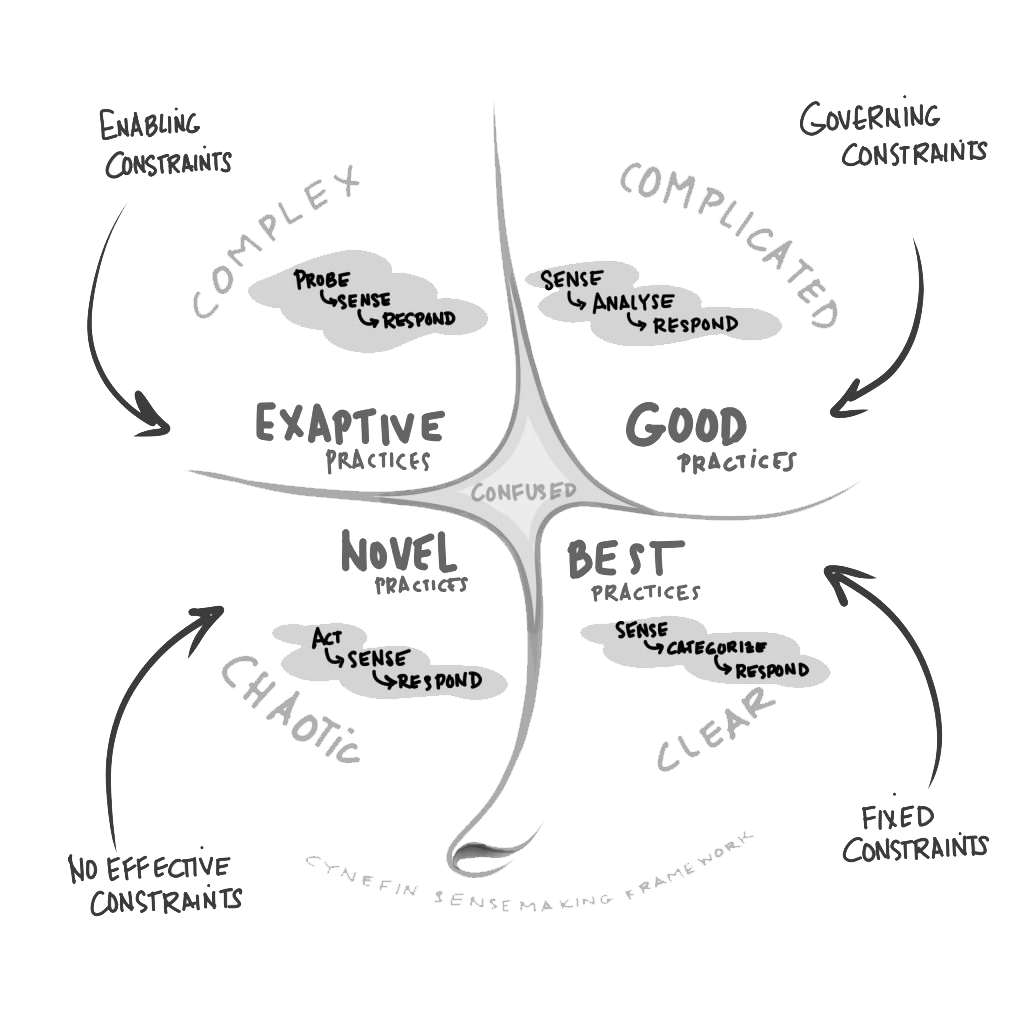

Organizations are, indeed, comfortable with linearity: planning and traditional sense, analyze, respond. And this makes it difficult to apprehend things that don’t fit the pre-established paradigms. Agile Software development approach like Scrum offers some relief but only as a transitional medium (liminal space) and is not sufficient to understand what to do in the first place (sensemaking & orientation):

“The strength of approaches like Scrum is holding things in a liminal state long enough to become right before they move to complicated.” — Dave Snowden on Liminality in Cynefin and Moving beyond Agile to Agility

Sensemaking is what is needed to make sense of a context, reveal possibilities, and orientate decisions before moving to development. But this obviously counterintuitive in organizations oriented toward operational & governance constraints.

We only see what we expect to see.

A Way Forward: start from the current context, not your idealized future.

The space-for-action barrier seems an implacable realization from which the only way is simply to avoid contexts that would prevent you to act: needless to say, it is a doomed headlong rush.

Working with constraints is what we should master because they are (generally) useful and necessary for the organization to function. Organizations are used to approaches that fit in ordered and rather clear situations. The problems emerge when the context is ambiguous and necessitates sensemaking rather than good practices. But how do you move from good practices (governing constraints) to discovery/questioning (enabling constraints)?

In a recent article titled “Selling novelty”, Dave Snowden gives us some great insights, answering a Customer Experience Manager’s question about the practicality of convincing a C-Suite board to use an approach they never heard of (here Cynefin’s) to measure the customer experience, while they already have a very different idea of what should be done (i.e. using NPS).

- Don’t challenge [the idea/solution], it is where the buyer is, its a safe decision, you won’t change it.

- Start asking open questions [and show what others found as potential issues] —E.g. “It's a great statistical tool”, talking about NPS, “but how will you know what it means?” or “Other people I have talked to often find the score baffling as they don’t understand what the number means or why it is changing”.

- Try and find their motivation for this — have they been told to do it, or are they the sort of person who will only do what other people have done? That will tell you how much reassurance you have to give

- If you are comfortable start to suggest things as questions—“If your managers could do X, Y, Z” in other words, what your approach allows them to do, “would it help them make better decisions?”.

- Have you heard about [your approach]? Then explain and illustrate with metaphors.

- Suggest (but be subtle) that if this works s/he will be a hero, if it doesn’t nothing much will change anyway.

- Suggest [your approach] can not only provide what’s expected but can bring more (e.g. contextual meaning, for instance).

- Find champions working for the buyer who likes your ideas.

- Offer an experiment in which the buyer can bring in other people in the organization to share the risk.

- Feed-in a small amount of technical language (abduction in this case) explaining what it means and listen hard for said language to be fed back to you — when it is they will buy (adoption).

- If you have an agreement do not introduce any new information or ideas, close and move on.

- Be prepared for refusal. Be honest, say why you think they are wrong, and leave politely — they will call you back when the more traditional approach failed.

Note: I slightly modified the list to be less specific but I recommend you read the original article in full context and find more wisdom here.

Conclusion

The space-for-action barrier is a relative concept from which the effects depend on the initial context: there’s always a limit to which people (especially managers) will accept change & novelty.

The idea of “start from where the buyers are” is a powerful reminder that context matters. Accompanying change is more an open questioning than a force-fitting focus on arbitrary and externally defined targets & goals. Opening possibilities and proposing safe-to-fail experiments broaden-up and add-up to their current perspective(s) instead of subtracting/replacing it for a so-called idealistic “better world”.

Discussion