The Algorithms That Were Meant To Delight Us Locked Us Into Misinformation (Or Do They?)

AI, Cognitive Biases, User Experience Design, Ethics, And The Problem With The “Filter Bubble” Effect.

In her article on Medium's OnZero Publication, reporter Erin Schumaker talks about conspiracy theories and why they work so well on social networks.

She describes what are the issues of moderating content for big Tech companies such as Facebook, either it is by the actions of real humans or it is the use of fully autonomous algorithms. The latter is, however, not yet ready and humans are still needed to review pre-filtered content to be moderated.

One of the issues relates to the fact that it is really hard to come with clear criteria to determine if a content is really worthy or not. Absolute criteria don't take into account specificities –and have already shown their limits– and it is still hard for algorithms to understand properly the contexts and all the subtleties of our languages. All of this is really well explained and sourced in the article and I invite you to take it a look.

The Filter Bubble Effect

Further on the article, E. Schumaker talks about the current issues related to the use of algorithms in social networks:

“That social networks like Facebook tend to create an echo chamber—or what Eli Pariser famously called a 'filter bubble'—isn’t by accident. It’s the inevitable result of the attention economy.”

– Erin Schumaker, Why Conspiracy Theories Work so Well on Facebook

As said, this "filter bubble" effect was first coined by Eli Pariser in his book “The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think”. It is worth mentioning that E. Pariser is known for his internet activism and his 2011 TED Talk largely helped to popularize the concept of the filter bubble.

The whole topic is emotionally charged and pretty touchy: we are talking about one of the core elements of the current tech giants' strategy. What some calls the “attention economy”. Is it a conscious move of those companies? Do they have an evil plan to take over the world?

To read: How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know, Farnam Street

Well, of course, the reality is way more nuanced than that. In fact, those algorithms were meant to improve our experience and ease our journey through their services. Those companies invest a lot to ensure frictionless and delightful experiences to their users.

This is not an altruist position tho, as fewer frictions and a more enjoyable experience make you stay longer, use more, and increases chances that you come back to the same service or product next time. There are no evil intentions here, but the lack of ethical considerations lead to visible side-effects and obvious concerns at a society-scale level.

Anyway, the lack of knowledge of the public on this topic in addition to a bit of misinformation fuel imaginations, conspiracy theories, and fears in the public discussion.

To read: Algorithms and the Filter Bubble Ruining Your Online Experience?, HuffPost

Same Concept, Different Context.

In 2008 (3 years before E. Pariser's book) was released the book “Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment”, written by Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Joseph N. Cappella, both professor of communication, respectively at the University of Maryland and Annenberg School for Communication.

This book offered a criticism of the relationship between the politics and medias during the 2008 U.S. elections, showing what co-author J. Cappella calls a “Spiral of Cynicism” (on dedicated paper and a book), or how journalistic political point of views can create self-protective enclave amongst a population, shielding those groups from other information sources and promoting highly negative views toward opponents. The term “Echo Chamber” became then quite popular. The concept of “filter bubble” is known to be similar in meaning, while it applies to the context of social networks –with the addition of a technological dimension.

To read: The Echo-Chamber Effect, New York Times

If the “Echo Chamber” is largely known by the public –as well as the “filter bubble”– due to its large media coverage, however, some of the studies that support the concept are criticized amongst the scientific community. Specifically, the “Spiral of Cynicism”: In a study of the Danish's political news coverage of an EU summit taking place in Denmark, Claes de Vreese, Professor of political communication at the University of Amsterdam, found very small evidence to support the claimed effect.

“In sum, when the assumption that cynicism is detrimental to political participation is evaluated against the available evidence, there is in fact modest empirical evidence to support a direct link between high levels of cynicism and low levels of turnout. So far, we can only conclude that strategic news under certain circumstances can contribute to cynicism about politics, but a critical and reflexive citizenry might in fact be rather good news.”

– Claes de Vreese, The Spiral of Cynicism Reconsidered

In fact, the specificities of the first study on “Echo Chambers” can't be overlooked: one political scene (U.S.), during a specific context (2008 elections), on specific medias, should prevent us from overgeneralizing a phenomenon.

Besides, it is worth noting that the concept of “Echo Chamber” describes a socio-psychological effect called “Ingroups and outgroups”. An ingroup is a social group to which one psychologically identifies as being a member, and an outgroup is any social group exterior to the ingroup. For instance, think about your favorite sports team, in which you probably identify yourself. This is your ingroup. By opposition, the other teams are the outgroups.

This topic is well researched and explains very well the polarisation in debates (i.e. ideological or political), as well as several other intergroup biases. The “Echo Chambers” concept is a questionable appropriation of the “ingroups and outgroups” in the Political Communication realm.

The Race For Frictionless, Delightful, And Addictive Experiences

As explained earlier, these algorithms are originally meant to improve our experience and ease our journey through those companies' online products and services. And it is important to understand some core principles at the root of this purpose.

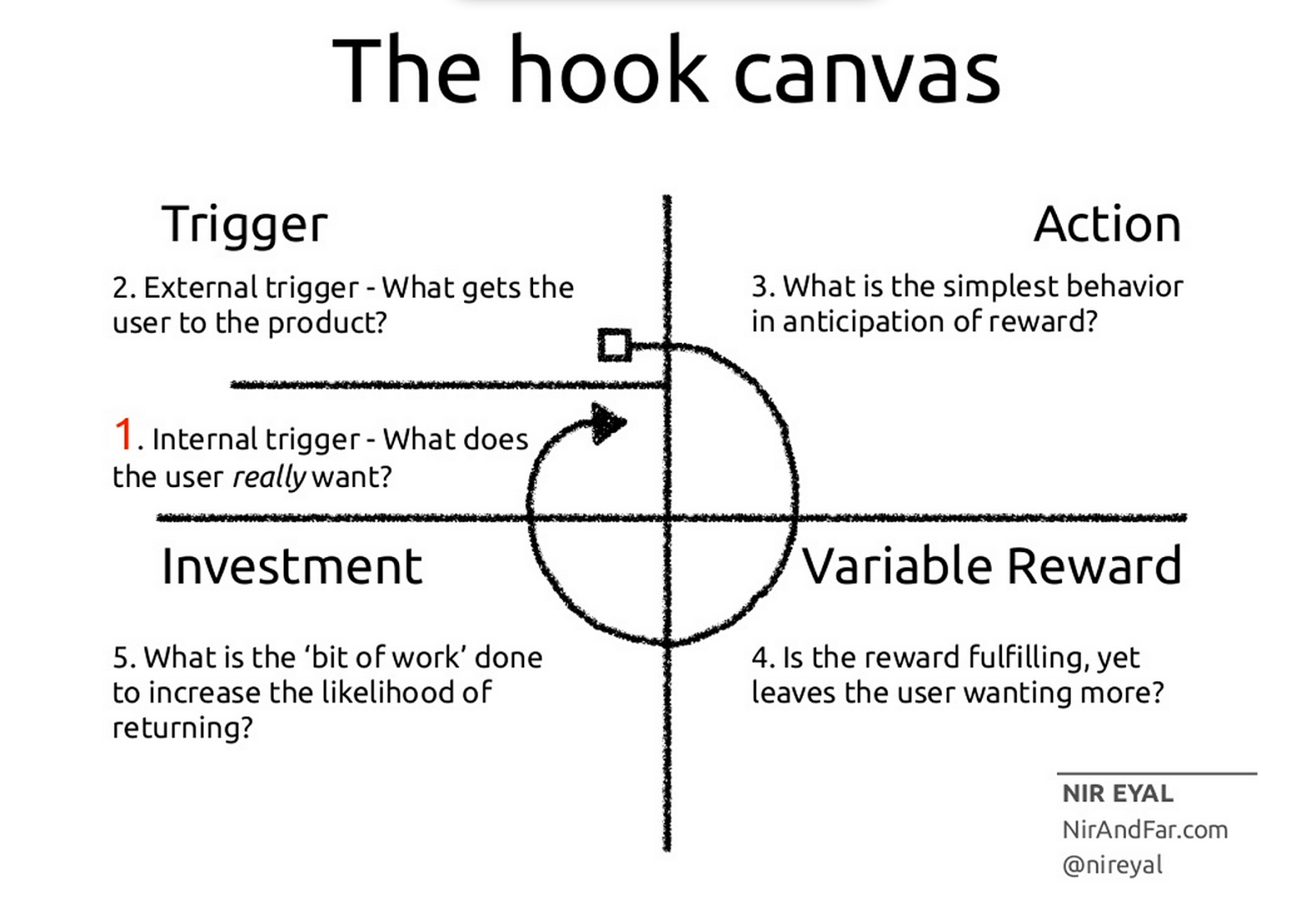

Nir Eyal, psychologist and Behavioral Designer, explains in his book “Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products” how companies such as Facebook, Google, etc. use a simple yet effective model that exploits our brain's addiction to habits.

His work resulted in a framework called the "Hook Canvas" and that shows how, by going through four specific stages, a product could be designed to create habits which will make you more likely to come back to the same product again and again.

To simplify, when you are in a specific state, let's say boredom (the internal trigger), you are more sensitive to certain external trigger that may catch your curiosity/interest –let's say a notification, an email, etc.

This trigger provides generally an action that will probably send you through the product and will give you an “immediate reward”. Therefore, the reason you came is fulfilled but you want more, and everything is made for that.

Perhaps the product will ask you to enter information, or actively participate (i.e. share/like/comment) and by doing so, make you “invest” in the product (i.e. emotionally). This investment increases chances that you come back to the product next time the same conditions occurs. Time over time, this reinforcement loop “hook” you into an addictive habit state.

However, Nir Eyal reminds us that companies which use such models have huge ethical responsibilities:

“What are the ethical responsibilities of companies that are able to manipulate human behavior on a massive scale? It’s a question one hopes technologists and designers ask themselves [...]

The tech industry needs a new ethical bar. [...] I humbly propose the “regret test.”

If we’re unsure of using an ethically questionable tactic, 'If people knew everything the product designer knows, would they still execute the intended behavior? Are they likely to regret doing this?'.

If users would regret taking the action, the technique fails the regret test and shouldn’t be built into the product, because it manipulated people into doing something they didn’t want to do.”

– Nir Eyal in “Want to Design User Behavior? Pass the ‘Regret Test’ First”

Facebook, Google, Uber, and many others are using similar models to understand people's behavior and make you stay longer on their platform, ensuring you invest enough in those to come back, read, share, like, comment, etc.

The Science Behind The Effect

Do science back up the whole concept of “filter bubble”? Well, yes and no. Scientific consensus has yet to come on that topic and several studies have indeed attested the effect, but there is a catch. A subtle one, but still important. Can you find the problem? Let's play!

First, here are some relevant studies we can find on the topic:

1) DuckDuckGo’s study of the filter bubble leads to interesting results on how Google algorithms pick the content that appears in your search results. Well, of course, their motivation is obviously questionable because of their position against Google.

2) This experiment (in French) — “I tested the algorithms of Facebook and it quickly degenerated”, by Journalist Jeff Yates at Radio Canada — lead to some impressive differences between the test and control groups. However, because of the date of this article, the results should be taken carefully.

3) This very well documented paper explores how different democracy theories affect the filter bubble. It also describes some tools and tactics used today to fight the filter bubble effect and their effectiveness and limitations.

Excerpt from the paper's conclusion:

“[The] viewpoint diversity is improved not only by aiming for consensus and hearing pro/con arguments, but also allowing the minorities and marginal groups to reach a larger public or by ensuring that citizens are able to contest effectively. As we have mentioned earlier, minority reach could be a problem in social media for certain political cultures.”

– Engin Bozdag & Jeroen van den Hoven, Delft University of Technology.

4) This empirical research paper explores filter bubbles in the field of political opinions on Facebook. They concluded that Facebook increased exposition to different opinions. Yet, their work suffer from the affiliation of the main author with Facebook Labs. (Read the full paper for free here)

5) This large study from the University of Amsterdam points out the lack of studies and research being conducted outside of the U.S. system on the topic and highlights the links between a population's environment (political, societal, governmental, etc.) and certain aspects of the filter bubble effect.

Additional source: Two IViR studies included in Parliamentary paper on the future of independent journalism in the Netherlands

6) This study published in Oxford’s Public Opinion Quarterly (2016) concluded a limited implication of the algorithms in the “filter bubble effect”, stating that “the most extremely ideologically oriented users expose themselves to a high variety of information sources from the same ideology”. (Read the full paper for free here)

In other words, the study reminds us that the “filter bubble effect” exists without algorithms, as we’re keen to confirmation bias and cherry-picking.

Question: Now, can you see the problem with the claim around the “filter bubble”?

Conclusion & Discussion

As you can see, the scientific community does not yet agree on a consensus and there is still a debate on the exact degrees of impact of the algorithms on people behavior, beliefs, and ideologies.

As a reminder, what's the claim behind the “filter bubble” effect?

“[That's] what I'm calling the "filter bubble": that personal ecosystem of information that's been catered by these algorithms to who they think you are. ...

We turn to these personalization agents to sift through [information] for us automatically and try to pick out the useful bits. And that's fine as far as it goes. But the technology is invisible. We don't know who it thinks we are, what it thinks we're actually interested in.”

– Eli Pariser in an interview for The Atlantic

The main issue here is that even tho we are sure these algorithms do have an impact on what we're consuming on the internet, their impact is thought to be relatively marginal in most studies. People confuse correlation and causality. There is an effect, we can correlate it, but does it implies what's observed? Not necessarily.

Occam's razor –or the principle of parsimony– tells us that “simpler solutions are more likely to be correct than complex ones.” So, what could explain otherwise the observed effect? The last paper gives us a clue.

“[The] most extremely ideologically oriented users (2%) expose themselves to a high variety of information sources from the same ideology. This exposition occurs through direct browsing. Algorithms play no role.”

– Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption

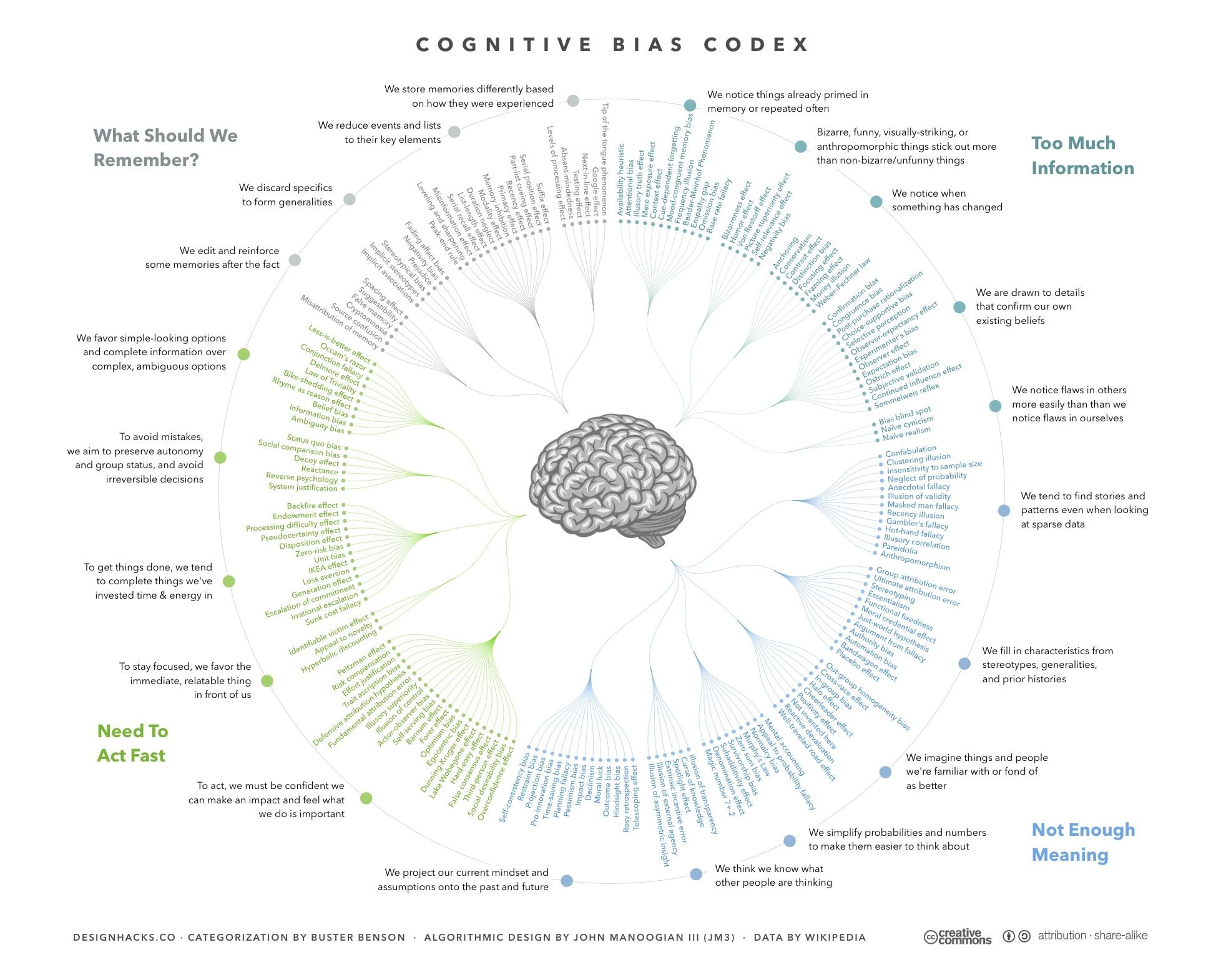

We have an already well-proven phenomenon that explains perfectly the observations: the human's cognitive biases. With an extensive list of hundreds of them, including the famous confirmation bias (or cherry-picking).

Yes, it is most likely probable that algorithms increase somehow –and depending of the context and many other variables– some of our biases. But most of the studies overlook a bit the human part of the equation.

Some Thoughts On How To Fix It

In this study, the researchers explore ways to influence the effect among a population, with the intent of reducing it. It shows interesting results, suggesting that awareness of the effect empowers the users, both in the understanding of mechanisms and control of the data stream they were exposed to.

What is interesting here is a very simple yet effective principle: if the service informs –by design– the user of its consumption type of information, this awareness helps him take “better” (or at least different) decisions.

Thank you for reading! 🙌

We believe that Business, Design, and Technology should all join forces to do what matters the most: answering people’s pains. This is where innovation lies!

Thanks for helping us share this message of hope and for supporting us!

References

- Why Conspiracy Theories Work so Well on Facebook, by Erin Schumaker

- Going Further On The “Filter Bubble” Effect, by Kevin Richard

- The filter bubble, Wikipedia

- Who's Eli Pariser, Wikipedia

- The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think, Amazon

- Eli Pariser: Beware online "filter bubbles", TED Talks

- Attention economy, Wikipedia

- Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment, Google Books

- Spiral of Cynicism, by Professor J. Cappella (1997)

- The Spiral of Cynicism Reconsidered, by Professor Claes de Vreese (2005)

- Faulty generalization, Wikipedia

- Ingroups and Outgroups in social Psychology, Wikipedia

- Ingroups and Outgroups: Group polarization, Wikipedia

- Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, by Nir Eyal (2014)

- How the brain controls our habits, MIT News (2012)

- Hooked: These Simple Habit-Forming Tricks Increased our App’s Retention by 53%, by Adam Moen on Medium

- The Hook Canvas (image)

- Reinforcement in behavioral psychology, Wikipedia

- Want to Design User Behavior? Pass the ‘Regret Test’ First, by Nir Eyal

- Measuring the "Filter Bubble": How Google is influencing what you click, by DuckDuckGo (2018)

- J'ai testé les algorithmes de Facebook et ça a rapidement dégénéré, by Jeff Yates at Radio-Canada (2017)

- Breaking the filter bubble: democracy and design, Ethics and Information Technology (2015)

- Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook, Science Issue 6239 “Political Science” (2015)

- Beyond the filter bubble: concepts, myths, evidence and issues for future debates, University of Amsterdam (2018)

- Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption, Oxford University's Public Opinion Quarterly (2016)

- The Filter Bubble, an interview of Eli Pariser in The Atlantic (2010)

- Correlation does not imply causation, Wikipedia

- Occam's razor, the law of parsimony, Wikipedia

- Cognitive bias, Wikipedia

- List of cognitive biases, Wikipedia

- Confirmation bias, Wikipedia

- Cherry picking, Wikipedia

- Understanding and controlling the filter bubble through interactive visualization: A user study, University of Saskatchewan – ResearchGate (2014)

Discussion