Organisation-wide design as systems practice: A path towards a distributed and integrative design practice.

Enterprise Design: building an ecosystem

This article proposes to approach Design in the face of organisational complexity (complex adaptive human systems) as a transdisciplinary integrative practice more than a narrow, domain or skill-specific, exclusive, and centralised point in the organisation.

Organising design (design management) is generally seen as an operationalization –and therefore compartmentation– of an organisational function. We isolate, rationalise, streamline, optimise, and measure for maximum efficiency. This works in a production paradigm.

But seeing Design for what outputs it produces in a linear fashion is narrow and limits its impact. Design can bring critical (re)thinking of what an organisation do; it can bring diversity and innovation in thinking & doing; it can create spaces for the emergence of unexpected ideas; and it can bring a new sense of agency, ownership, and responsibility to the people within an organisation. Design can fill a “soft fluid space” between functions, services, teams, people, for organisational regeneration & agility — and reframing the organisation as an intentional complex human system and giving it space to breathe and reflect.

Beyond organising people, designing ‘spaces’ for interactions

Organising “the design people” (designers) and the “design work” can be seen both in a formal AND informal way:

- Tight relationship: People involved in specific activities (e.g. projects, products, etc.);

- Loose relationship: People that gravitate around those activities (e.g. researchers, ops, facilitators, etc.).

But beyond “people” and “roles” we should even more so think of design in an organisation in terms of spaces and constraints for enabling different types of outcomes: from specific space for activity-focused practices to informal/unbounded space for connecting ideas, people, and increasing serendipity; from synchronous to asynchronous; and anything in between.

This allows us to shift our attention from individuals to interactions (and more specifically, “the kind of interactions we want to see”), which is ethically preferable:

Framing things from an individual’s perspective implies at some point, imposing them expectations (ours, the organisation’s), and when misalignment, expecting people to change (when we’re not asking them directly), whereas, shifting the perspective in terms of interactions within a space (be it physical, virtual, social, etc.) enable individual agency & autonomy within or given certain constraints which, depending on the context, allows divergence, diversity of thoughts, and heterogeneity.

These kinds of soft spaces can become the “dark energy” of an organisation, so to speak, imperceptible but actively influencing it through its indirect effects.

Soft Spaces and enabling constraints

I use the term “soft space” here as a concept repurposing from urban & policy planning, therefore not stricto sensu. The term arise from academic literature and was coined by Graham Haughton and Philip Allmendinger in their study of spatial planning and the evolution of governance practices in policymaking.

In their 2008 paper “The Soft Spaces of Local Economic Development” in which they examine the connections between soft spaces, soft outcomes and soft infrastructure in the UK’s sub-national economic development policy, they explain:

Formal planning mechanisms with their legal responsibilities are primarily rooted in local and (to a lesser extent) regional government. These are the hard spaces of governance activity, involving statutory responsibilities, linked to legal obligations including democratic engagement and consultation, all of which take time, and come with a particular set of public and professional expectations around their choreography. This is fine and necessary – but for many politicians and their advisors, it also looks to be slow, bureaucratic and rigid. There is also a mismatch between the spatial scales at which such planning is undertaken and the more amorphous, fluid and functional requirements of development and cross-sectoral working.

And this is where the emergent alternative administrative geographies, or the soft spaces of governance, have a role to play, providing a series of alternative institutional spaces in which to imagine possibilities for future place making. In a sense, we’ve had them for some years now – the Urban Development Corporations of old, followed by inner city Task Forces, City Challenge areas. More recently though we have seen a trend towards commissioning area ‘Masterplans’, plus all those pilots, prototypes and other brave new world experiments such as Employment Zones and New Deal for Communities. These new institutional forms and spaces are invariably mandated to ‘break free’ of past rigidities, to introduce innovative thinking and new practices that can be learned from and adopted elsewhere.

We want to argue three things here in relation to soft spaces. First, this is a deliberate attempt to insert new opportunities for creative thinking, particularly in areas where public engagement and cross-sectoral consultation has seen entrenched oppositional forces either slowing down or freezing out most forms of new development.

Second, that the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ spaces of governance are mutually constitutive. One cannot work without the other. The aim is not to remove ‘hard’ institutional spaces with new ‘softer’ ones, rather to create complementary and potentially competing opportunities for development activities to focus around, whether at some kind of ‘sub’ regional or ‘sub’ local government scale.

Third, the soft spaces of governance are becoming more numerous and more important as part of the institutional landscape of regeneration.

Paraphrasing, soft spaces are defined as informal opportunities and interactions within a formal framework that connect people, ideas, levels of intervention, etc. and allow them to make a coherent understanding of the situations and prepare for the actions to be undertaken within the formal “hard space”, the framework under which they operate.

Informal collective sense-making & change-making is important because we share and elaborate (more than one might expect) more than what we can formalise, each individual being both participant and interpreter of the emergent construct. This process can’t be formalised and operationalised in the hard space, rather it is the necessary input that the system awaits. If you aim at increasing your organisation’s agility –meaning its capacity to sense and respond to change over time– one has to acknowledge that complexity (of informal interactions) cannot be reduced without losing information, and working with the inherent ambiguity of human interactions means that things happen outside of the formal system anyway.

Talking about complexity, I want to draw here a relevant link between soft spaces (from policy planning) and constraints in complexity thinking. This is relevant because this informs my usage of the term in the context of this discussion.

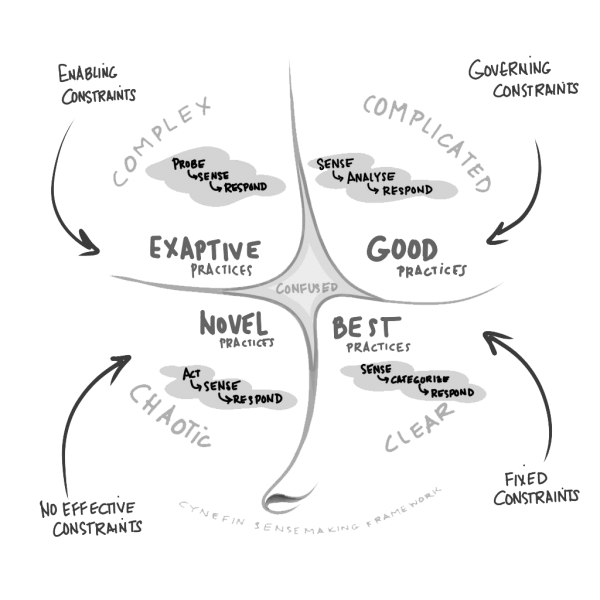

In the publication “Managing complexity (and chaos) in times of crisis”, a joint effort between the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service, and the Cynefin® Centre, the following types of constraints are described:

- Governing/Enabling Constraints: laws, rules, and codes create governing constraints. They give a sense of stability but are sensitive to change. Heuristics and principles, on the other side, provide guidance while allowing for distributed decision-making.

- Internal/External Constraints: insects have exo-skeletons which limit the size to which they can grow but provide a clearly visible structure; mammals have an endo-skeleton which makes them all self-similar but with a wider variety and fewer limitations on growth. Organisation design tends to focus on creating a skeleton, or scaffolding, and ‘points of coherence’ around which unities interact with each other and with the scaffolding itself. This is the case of ritualized meetings, performance evaluations, career assessments, etc. As far as external boundaries think markets, resources, social foundations, and environmental ceilings.

- Connecting/Containing Constraints: connections, like hashtags in knowledge management and links in networks, provide a flexible and adaptive structure but at the cost of visibility and control. Containers, like categories, spreadsheets cells, and departments, provide clear, reassuring boundary conditions. Changing connections between people and organisational units is less costly than trying to restructure or reorganize departments. As new connections start to provide new ways of dealing with issues, then the constraints can be tightened and eventually formalized into new units and departments.

- Rigid/Flexible/Permeable Constraints: deadlines are an example of constraints that are usually intended to be rigid. Flexi-time is a malleable way to manage attendance at work. Rigid structures resist until their design conditions are exceeded at which point they break catastrophically. In contrast, flexible structures adapt to stress and conditions of constant change. Rigid and flexible boundaries increase their resilience with permeability or special conditions that allow for exceptions, but permeability brings the possibility of clogs, i.e. too many people applying for or expecting exceptions.

- Dark Constraints: (a reference to dark energy or dark matter) we can see the effect of a constraint but we don’t know the cause. Dark constraints are like the several hidden meanings a term can assume for different people. When we mention a term and we see different reactions, we see dark constraints at work. Narratives are powerful antidotes against dark constraints. We can also get a sense of the risk going forward by modeling how much of the past we can explain by the constraints we are aware of. The more we can’t explain the less we can monitor, the more likely unexpected and potentially catastrophic surprise.

Constraints emphasise the need to think in terms of space and not just individuals, as the concept of Soft spaces does in its own way. Contexts embed inherent constraints (unintentional) to which we can design our own (intentional). Similarly, contexts come with inherent boundaries to which new boundaries can emerge (add, redefine, subtract).

Scaffolding and attractors

Other useful metaphors for thinking in terms of “Design”, “Soft Spaces”, and “Constraints” are the concepts of scaffolding and strange attractors.

A scaffolding is a structure, not meant to last, and that serves as a support to grow, build, or repair [something], usually the end-structure meant to last. The obvious example that comes to mind is in architecture & construction, but such structures can also be found in nature, as part of plants ecosystem for instance, and are used in medical application research.

In other words, a scaffolding is an enabler. Furthermore, we should be able to remove the scaffold (or let it decay) and whatever we helped grow should sustain itself. Funnily enough, we sometimes build scaffoldings that we mistake for the end structure, like say, our dear design processes.

Designing soft spaces means supporting and growing something bigger.

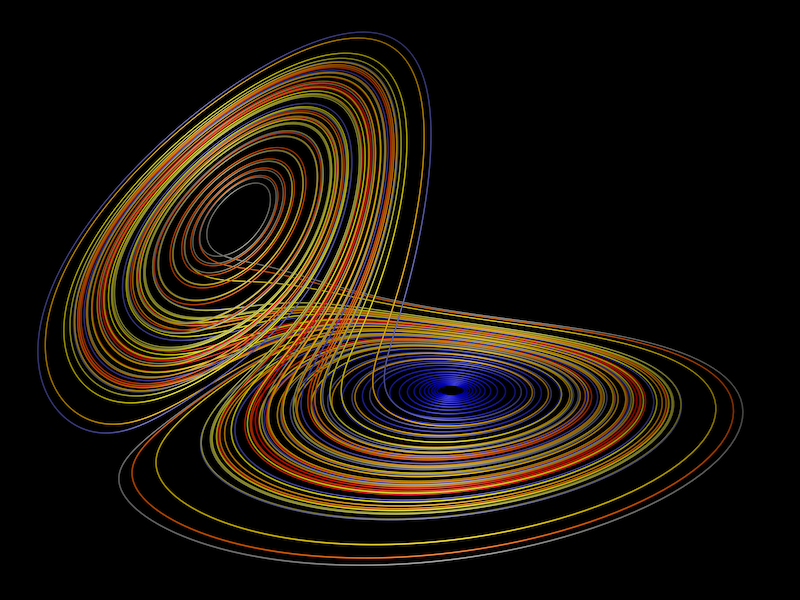

Attractors are defined as “a set of states towards which a system tend to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions”. In other words, an attractor exists by contrast or negative, as it is the mere result of the unexpected and unpredictable paths, of all possible paths, elements of a system tend to take. It displays a common pattern (despite the unpredictability of the system), although filled in with diversity. In an organisation, attractors happen to be “attractors” because of how information tends to revolve around –such as in narrative research, a trope is a form of attractor.

A form of attractor would be buzzwords, like say “new ways of working”, attracts a wide diversity of narratives, which taken in details might be contradicting each other and/or are informed by very different ideas & backgrounds, but taken as a whole is coherent. Another attractor could be in the form of cities, attracting a diversity of people, businesses, organisations, resources, infrastructures, etc. This diversity allows for divergence although revolving around the same point of coherence (the city), is thought to be a key factor in what makes cities more likely to enable inclusive & responsible innovation.

Designing soft spaces and their constraints for creative and unexpected divergence.

Creating soft spaces can play as attractors for a diversity of people, minds, thoughts, ideas, practices, experiences, (etc.) and as a scaffolding for long-lasting changes and innovations.

“Design excellence” as a distributed network, not a centralised point of reference

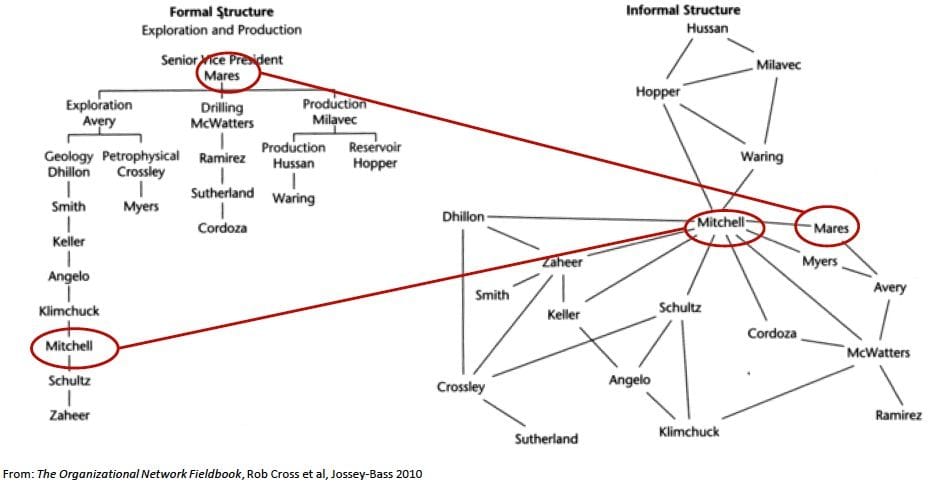

It happens that the very nature of a complex (wicked) problem is its state of entanglement with other problems/issues. When we look at an organisation (like say an enterprise and its context) as a complex adaptive system we realise that most ill-defined challenges, whether inside and/or outside of it, are first and foremost within the informal network that composes it –where ambiguity lies– not in its formal structure & processes. This is not much a problem than a reality we experience more or less consciously.

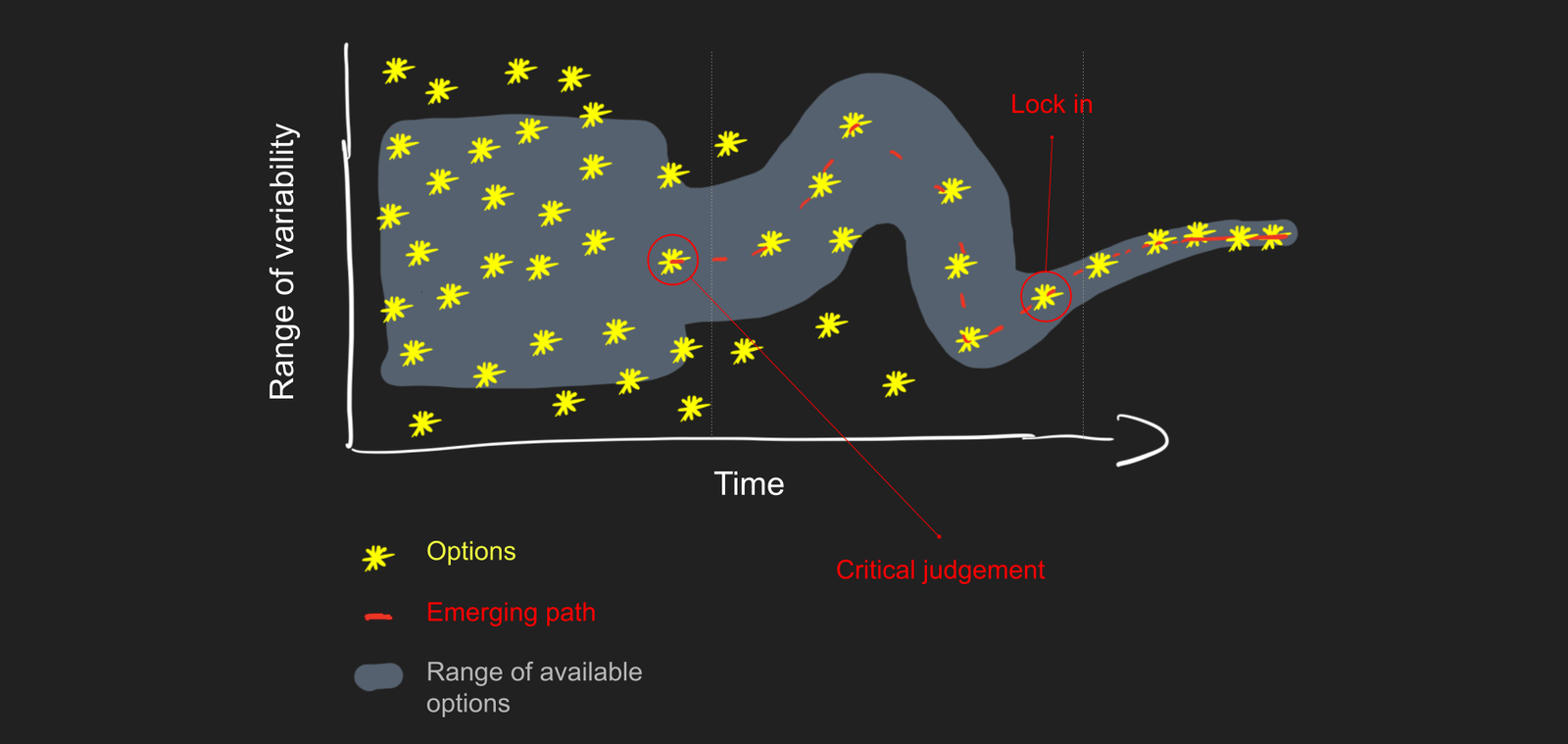

Complexity comes with context-sensitive and context-dependent aspects, flow of information, understandings, narratives, and so forth, that might contradict each other (hence the ambiguity). This means a diversity of people, in a diversity of contexts, with a diversity of perspectives, and a diversity of motivations. Traditional approaches tend to entitle one person or a small group of individuals to “solve problems”, in other words to interpret, extrapolate, generalise, strategise, plan, and act, and they often do so by creating supposedly “higher goals/objectives” by reduction or removal of context and externalisation of motivations in an attempt to make overall consistent decisions –thus, they become consistent regardless the context while imposing their extensions/implications to people. This is a funnel towards an expected single-point and optimal solution. And this is (probably) fine in many cases, except when you work on complex challenges because they hold a certain level of ambiguity that cannot be resolved through analysis and reduction to one single “good” answer –instead, complex challenges allow several potential “good answers” to co-exist at the same time (here again, ambiguity).

Systematically aiming for funnelling down “problems” to one solution (see “Funnelling vs Layering”) that is supposed to fit many diverse contexts, understandings, and motivations is likely to lead at best to “premature convergence” (see here, here, and there).

“In evolutionary algorithm, premature convergence means that a population (for an optimisation problem) converged too early, resulting in being stuck into a local minima or maxima state. This situation arise due to loss of diversity among individuals of the population.

Techniques to avoid premature convergence is to maintain diversity among individuals of the population; Using archive and designing efficient crossover operators.” – source

Understanding an organisation as first of all a human (socio-technical) complex system, being itself surrounded by other human systems, means we cannot subtract an inherent form of tacit ambiguity and complexity. A good example of that is the fact that although a company can be defined as a formal structure, say a hierarchy and/or some operationalisation processes, it is also defined by its informal structure (its network) at the same time.

As I further develop in The Explorer Framework, distribution is a necessary feature of a network. This means in an organisation:

“Not everyone has knowledge of or is aware of the same things, at the same time, in the same way.” This is not (necessarily) a matter of hierarchy: consider instead how formal and informal networks work and influence the flow of information.

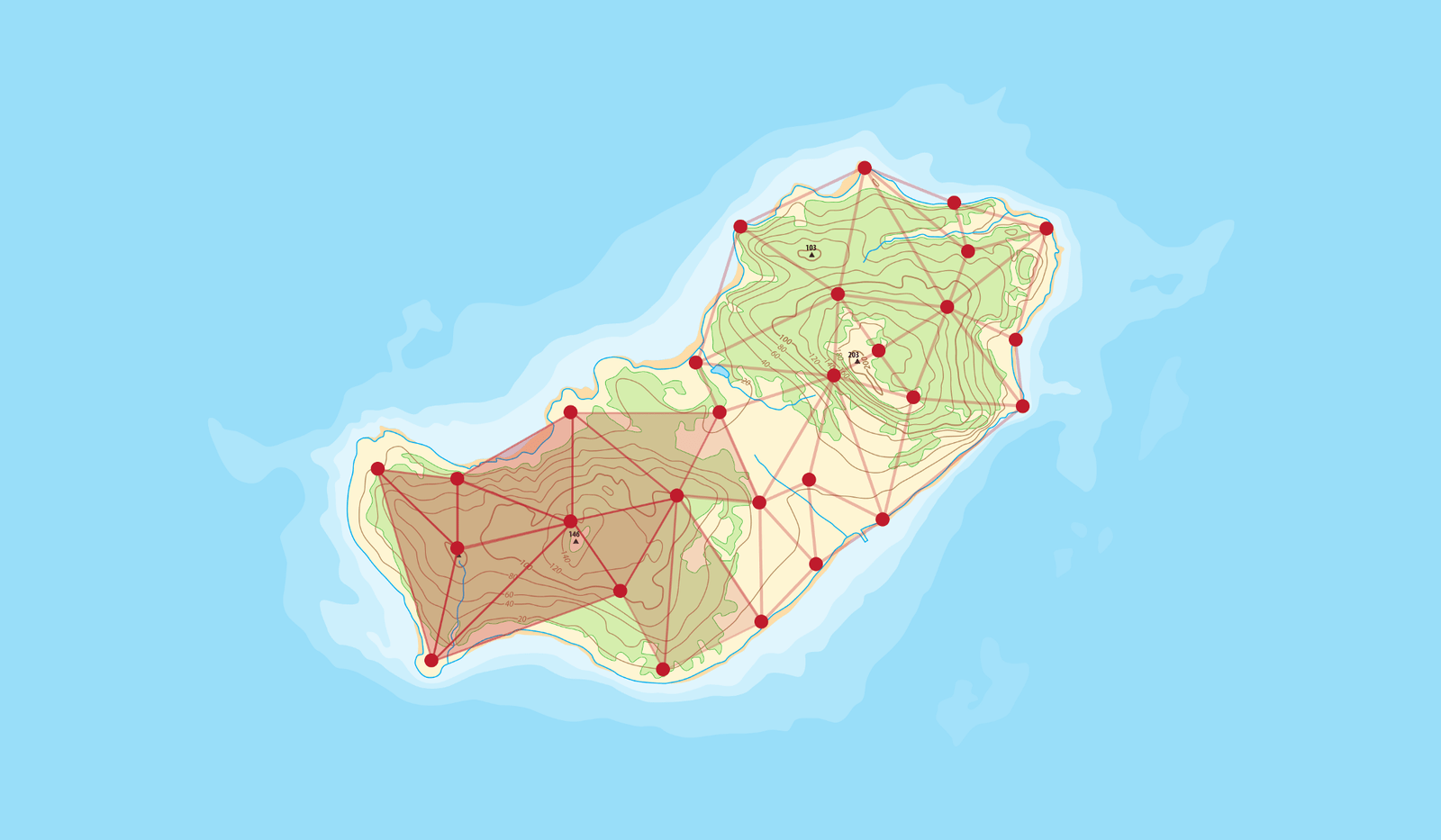

Like an island might possess shores, forests, rivers, mountains, abrupt cliffs, (etc.) organisations’ complexity, activities, and processes are both informed by the larger context of the organisation itself as well as the local specificities that people are facing.” – The Explorer Guide, Design & Critical Thinking

Counterintuitively, research tells us that the “viral contagion” of ideas and thus individuals’ perception of change or novelty primarily works through the informal & tacit human network. At this point, it is interesting to note that many of our practices revolve around the formal structures/processes of an organisation (despite what we know). One good reason for this is that it certainly seems easier to do so because it gives a sense of certainty & predictability in a linear chain of actions (apparent causality).

Building a local and contextual shared understanding

Having explained the role of informal networks in organisations and the importance of key concepts such as soft spaces, constraints, scaffolding, and attractors, we can now converge to application & practice. One aspect to understand is that there is a difference between knowing how a system works and acting upon this knowledge. It is already difficult enough for one person, let alone for a group or an organisation.

One thing is that although we can define boundaries, map out the system of interactions within those boundaries, devise a course of actions to intervene, etc. it is first rarely the case that one group of individuals is entitled to do that work; and secondly, we fall in the risk mentioned earlier of interpretation, removal of context, seeking consistency over coherency.

Another thing, as known in rationality, is that there is a threshold for which the cost of knowing supersedes the cost of acting and vice-versa (see epistemic & instrumental rationality). Acting without knowledge puts one at risk* of misalignment with what should be done knowing the context’s conditions; Knowing without acting puts one at risk* of running out of (or closing all) options when acting would have maintained/enabled more options in the long run;*risk being defined by the context. Mastering where to put the threshold comes with praxis.

As shown earlier, different contexts imply different approaches, and going down the rabbit hole of systems mapping isn’t always the “good” (let alone “best”) way to approach complex challenges. In fact, the map as an artefact is not really important here, it is what it enables people to do that actually matters (sorry for this quasi truism as this can be said to almost all design artefact) and a map is as good as what it describes –i.e. a map usually describes topographical & infrastructural elements because they are not likely to change drastically over time; and indirectly poses tangible constraints (again) to what is possible within a certain area.

Here “coherence” is most often than not preferable over absolute accuracy and what matters is the process that enables a collective understanding of the challenge at hand and what we could possibly do about it rather than expandable & rigid artefact. And this collective understanding & shared meaning creation (sense-making) has to happen more than once, as our actions impact the context we are working in, changing its conditions –in other words, there is no optimal solution. Here, we want good enough knowledge for good enough actions, and soft spaces host the necessary conditions (enabling constraints) for this knowledge and meaning to happen.

We also want that knowledge to match field reality, the levels of the landscape in which we operate. As explained earlier, certain things make sense only to a certain point in the system and generalising this understanding (to other points in the system) won’t necessarily help make good decisions. This means we need to create knowledge and “bias toward action“ (intrinsic motivation) at a local level while keeping an overall coherency.

Distributed design, ownership, and responsibility: a better ethical framework for complex & interconnected challenges and to build trust & autonomy within an organisation.

An interesting way to do so is to build a “sensory network”, an intentional network of people, that might grow/evolve over time as you navigate the challenge, that allows you to connect the different perspectives of the challenge (or organisation) and to sense & act at local points.

This approach brings autonomy and a sense of ownership to people that face a local “reality“ of the challenge, enabling them to both inform the network and make decisions at their local level is a powerful and inclusive way to bring a diverse (yet coherent) set of actions, solutions, or what I would call mediums for interactions to catalyse changes.

Here, we give them the autonomy to define what is the things they/we (both) want to see more often (the “good outcomes”) and those we want less (the “bad outcomes”) based on their experience. Furthermore, we give them responsibility as we ask the network to monitor changes over time given the actions undertaken: “are we heading in the right direction?”.

This approach keeps the burden of interpretation at a local level (not in the hand of a single individual), that is to say where the experience & context lies, while enabling the creation of shared understanding (at different levels and in between different groups) through informal soft spaces.

Soft spaces as oscillations in the system

Seeing information as energy allows one to treat it with similar properties. Energy cannot be created nor deleted, only transformed. More so, energy can move through mediums (energy vectors), which are not all equal in terms of effectiveness & efficiency.

Formal and informal ways to gather and/or treat information constrain information in different ways, offering different losses & gains on the net output, affecting scope and scale of understanding.

For instance, an undirected, unbonded conversation is an informal way to gather information communicating a lot of depth & details, allowing context-blending (people can relate to similar personal experiences) and providing flexible enabling constraints through stories. The downside is added noise in the information processing.

On the other side of the spectrum, directed, motivated, goal-oriented methods like, say, a survey or some forms of interviews and workshops formalise information through predetermined/anticipated inputs, filtering information and providing more rigid constraints.

There is a relationship between how we are making sense of our context and what we can do about this understanding.

As explained earlier, soft spaces offer opportunities for informal, unguided/unbounded connections between people, ideas, practices, and thus flow of information. Soft spaces should not be seen with benefits on their own, but rather in combination with other approaches and more formal approaches & processes.

For instance, distributing design practices can be seen as a network forming activity that can be achieved with formal means (e.g. a chat tools, emails, etc.) mixed with informal spaces for discussions that can prompt directed and/or semi-guided spaces (e.g. workshops, hackathon, etc.) dedicated at tackling a specific issue.

Building such a network can be done through various means and mediums, but it is worth mentioning they will not all allow for the same type of interactions impacting the type of information that can be gathered, the effectiveness of the overall network response, and our perception of the information.

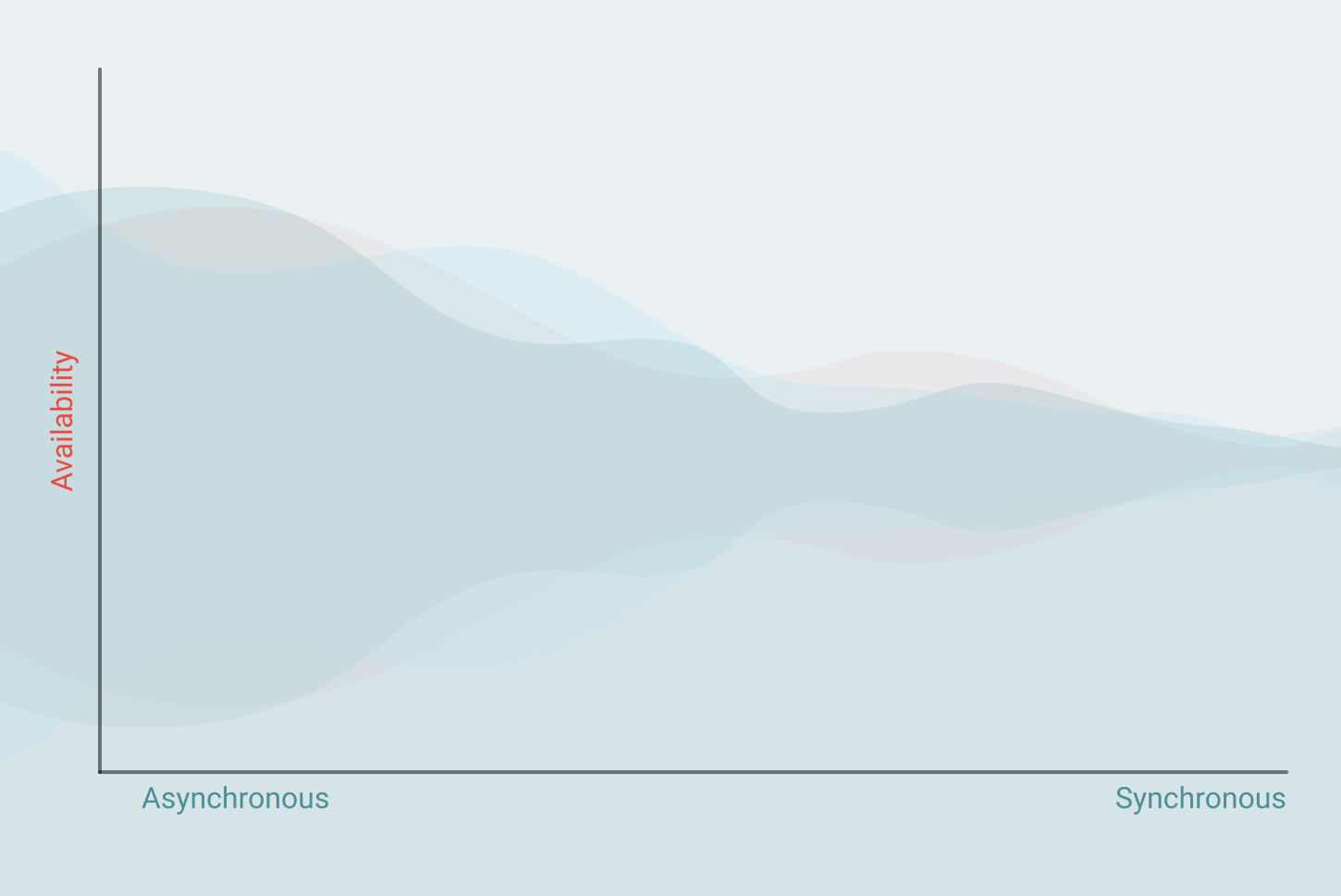

- Synchronicity allows for immediate, direct, prompted feedback which tends to be also very localised and context-specific. It is extremely useful contextually but also energy-intensive and, therefore, generally hard to sustain for a long period of time.

- Asynchronicity allows for delayed, indirect, unprompted feedback. More energy-effective but also less context-specific, it can be run over long periods of time. This tends to allow to build a much broader sense of the patterns at play.

- Availability (perceived instantaneity) will define the effort (friction) that the network will have to take in order to generate feedback. The more asynchronous, the greater we want perceived instantaneity because of delayed response from the feedback mechanism.

Focus on practice & safe-to-fail spaces over generic certifications

For the most part of our day-to-day functioning, human knowledge is context-sensitive (see contextualism) and tacit, even in “expert domains“. As discussed earlier about the constraints of information, the formalisation of knowledge brings reduction in noise but also losses in context-specificity of the information (see situational knowledge/awareness).

Certifications, for instance, tend to condense knowledge in a highly digestible, formal, standardised, and linear way to cover so-called “basics” in the least amount of time in the attempt to produce rapidly an “operational workforce”, if I may formulate it this way. The criticism isn’t on the existence/validity of such “basics”, but the rather that for each individual thrown on the market with a certification, we rarely take into account the necessary time required to become truly “operational” –what we call experience– which even with variability between individuals is incompressible (meaning at least some is necessary) and should (probably) be seen as an investment, a trade-off, rather than a cost to a learning experience.

In other words, experience is context-sensitive knowledge, and what we call “basics” in a discipline makes mainly sense in regard to their applicability, the context in which we act.

Experience comes with practice, and practice with opportunities –and with unequal accessibility, let’s face it. Formal spaces tend to have formal and predetermined expectations on results & outcomes (in a linear fashion), which raise expectations on individual experience & expertise (and increase inequality of access over time). Soft spaces offer learning capabilities and safe-to-fail environments, and by playing with constraints, can offer a fertile ground for meaningful training.

There’s a military analogy here: small crews, training in the field, repetitive movements, situational heuristics, etc. to build trust, confidence, competency, and approach groups & individuals’ practice learning.

Approaching the organisation as islands and archipelagos

We can use the metaphor of exploring islands to derive an epistemological framework and some heuristics as we are navigating complex challenges, together with his idea of soft spaces.

When encountering an island on the horizon, you don’t know how big it is, or what to find there. If you were to land on its shore, you wouldn’t know where you are because you don’t have any point of reference yet.

An island is a context, a subject, something you can’t ignore, solve, or remove. There are people, an ecosystem, infrastructures, a topography, a local weather system, things that are unique, and others that are generic. Beyond these, there are, not visible at first glance, relationships between them that determine values and meanings in this specific context. This is your challenge, the context of the problem you are facing. This is its physical (and virtual), yet often imperceptible, space. As for problems, from where you are, looking at the island, you can get a rough idea of some of its features, but you’re too far to understand all the relationships at play there: you’re still in a confused state (or aporatic state).

Several contexts, challenges, or problems can be found close to each other, like an archipelago. An archipelago is a coherent group of islands — or a coherent group of contexts. Each island/context can be very different in size and ecosystem but are related to each other in a fundamental way.

Adjacent possibles (see here) and aiming at indirect goals: What can be done here and now, that benefits people at a local level? (see also here, here, and there)

Thanks for reading!

This article has been influenced by my work and study on Design, Complexity thinking, Systems practices, and the discussions & collaboration with the Design & Critical Thinking Community. Some of the ideas discussed here draw from the Cynefin framework and concepts (see also here).

Discussion