Innovation By Design: A complexity-based understanding and provocation.

Hi everyone, Kevin here.

I often talk here about Design as a catalyst for organizations (and here), businesses, and at a much smaller scale, teams. Design is to me, a means to instigate change and impact (positively) our environment. This is why I also think this not the job of one person.

Because of this, I consider innovation in many ways similar to Design in terms of purpose. “Innovation” — whatever it translates to in your context — is another way of designing our environment toward an intent.

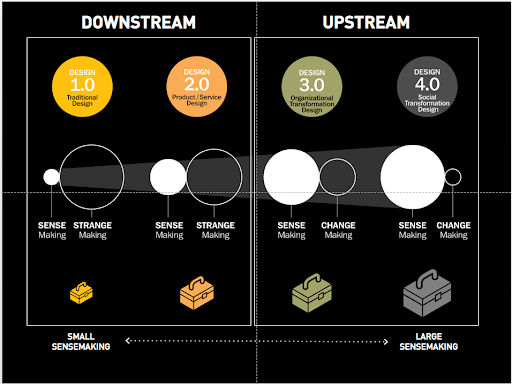

As I recently explored in “The Multiples Design Thinking” and “The Ethics Of Design Sprint”, the multiplicity of Design practices and the various level of complexity we’re facing when designing requires us to use different thinking styles to approach the challenges. We, as communities, create or adopt paradigms that allow us to more easily anticipate and navigate our environment.

In a given paradigm, we expect certain things to occur. As such, these paradigms are as much helpful than detrimental, because they limit our views to a set of predetermined expectations. Most of my criticisms against some “Design paradigms” are precisely this. When some of their proponents lure themselves (and their followers) by genuinely believing they can address any challenges in any environment, this is clear blindness toward the limitations of their paradigm.

The Design Sprint, Design Thinking, User-Centered Design, Lean, Agile, etc. are (more or less) constrained and motivated paradigms. Note that this is not an attempt to equivocate them: they are not intended to navigate the same level of complexity, or if so, they do it from different backgrounds. They are different. But they also share some characteristics and are all dependent on their environment.

So bear with me while we’ll try to understand them together.

Does Design Equal Innovation And Vice-versa?

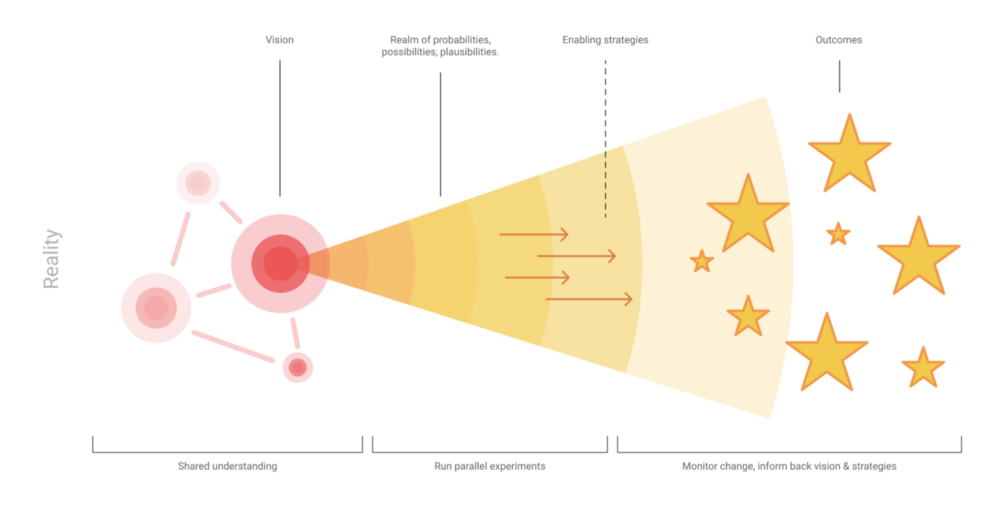

Design and innovation both share common goals. They both seek change, from a current state of a context (system) to a future-yet-undefined state. But their intents might differ in the type of outcomes they are seeking/expecting, although, note that the distinction here is more than blurry and there is a lot of overlaps.

Designers are often taught to, and therefore comfortable with, defining solutions. They devise such solutions from more or less disordered, unclear, messy context, the “problem”, and apply their skills to order things, make sense of them, and materialize a relatively clear & finite solution.

See the use of the problem → solution dichotomy here, predominant in the design world, and inherited from the industrial era. The huge trend toward Product Design in the tech industry is a perfect example of that “thinking style” legacy. Most of this “traditional” way of designing specifically seeks solutions that are (so-called) “tangible” or “concrete” — i.e. a product or a service (in the digital or physical meaning) with clear boundaries. These are clearly the most dominant characteristics of one largely shared design paradigm.

Although, as diversity exists in challenges, and so exists in the way of designing: from Service Design and Business Design to Organisational Design and Systems Design, there’s a huge variety of practices, knowledge, profiles, and backgrounds we can draw from the increase in complexity. And this is where the line between design, innovation, change, etc., is more than blurry.

“Design is an intent” — Jarred Spool

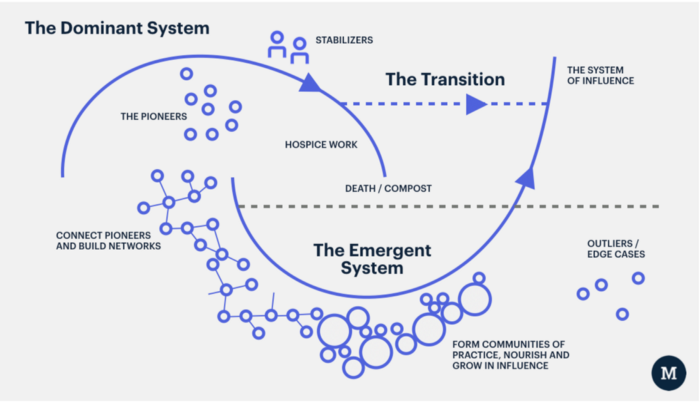

Innovation is an even less clear practice. They too work toward making sense of and ordering things, but not necessarily in the same way. While designers seem to seek change through a solution, innovators seem to seek change in a broader context: actions become mediums for change — this is why every solution isn’t an innovation. We can also probably draw a difference in scale here. But innovators become “designers” of some sort when they start devising solutions to support their actions. Borrowing from Open Innovation and Systems Change communities, the paradigm here would be more: challenges → intervention strategies.

Again, these are blurry lines and I don’t want to reduce the discussion to my short definitions. So please, share your thoughts in the comment!

Clearly, some people do both while being considered as either designers or innovators and, generally speaking, we can find profiles focused on broad challenges and more narrow problems on both “sides”.

Defining them as change agents seems to better reflect this ambiguity. If “design is an intent” then there are more anonymous and self-unaware designers than one might think.

Change agents have a normative role: they prescribe rules and preferable behaviors toward a specific context. They are moral agents and as such “ethics” are indivisible from their actions. Only the scale at which it applies vary.

On that point, maybe one more note: the broader & complex the challenge, the more diverse & multiple the group (and sometimes network) of people tackling it necessarily is (formal vs. informal). Ethics behooves on each agent, and more specifically upon the group as an entity, not upon one single individual (i.e. the designer). The fallacy of reducing ethical issues to an individual designer’s responsibility, as if one person could/should have such an agency/power, is precisely the type of thinking that led to today's issues.

But What Is Change Anyway?

Change (noun): “An act or process through which something becomes different.”

Change is, therefore, a transitional, moving, dynamic, and ongoing state. It brings a temporary disorder in a system. This state creates new (relative to the current context) opportunities for negative AND positive outcomes.

Innovation, Invention, Creation, Production.

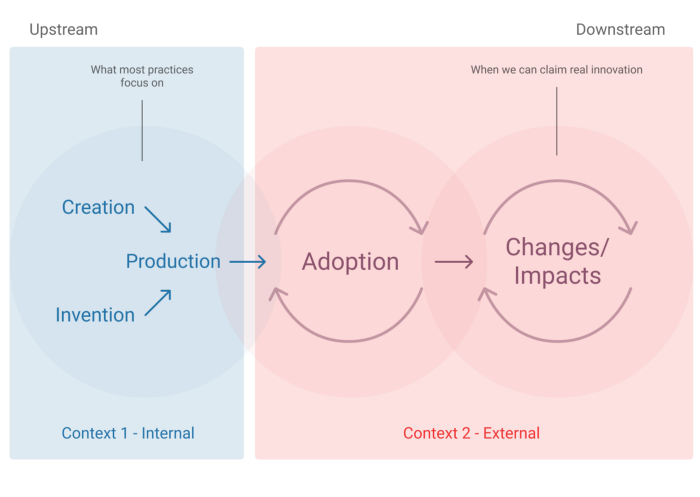

Some easily conflate notions like invention, creation, and production for the notion of innovation. But these are fundamentally different concepts.

“Innovation is about the creation of something that is both new and a value however it is also about its adoption and implementation so as to change some established way of doing things. […]

Innovation is different from pure creativity in that it is looking at both ends of the equation both the creation of something new and useful but also its adoption and usage within society so as to enable real change in the world around us” — Systems Innovation, an overview.

For instance, an invention is the result of any process aimed at creating or producing something, usually (but not necessarily) new. The novelty or existence of which does not necessarily lead to innovation — as we defined it earlier, a change in the context of the said invention.

The shortcut comes from the flawed reasoning that if most innovation seems to come from the “creation of something new” — in the sense of “the production of tangible artifacts” — therefore, creating new things is an innovation by itself.

The problem is that it is not a 1–1 causal relationship — all new things do not lead to significative changes — and reducing the outcomes of a change to one single event, maybe the most visible one to us, is narrowingly simplistic — a selection bias to the most salient (see Selection bias, Frequency illusion, Focusing effect, Salience bias, you named it!).

If an “innovation” is measured by the positive impact of changes in a context, then we must include all the events that led to these changes: it is more than a neatly defined “new thing”. As such, the value of an innovation is more than the sum of its constituents, and amongst other things, it lies in the relationships & interactions with its context (social, economic, technological, etc.).

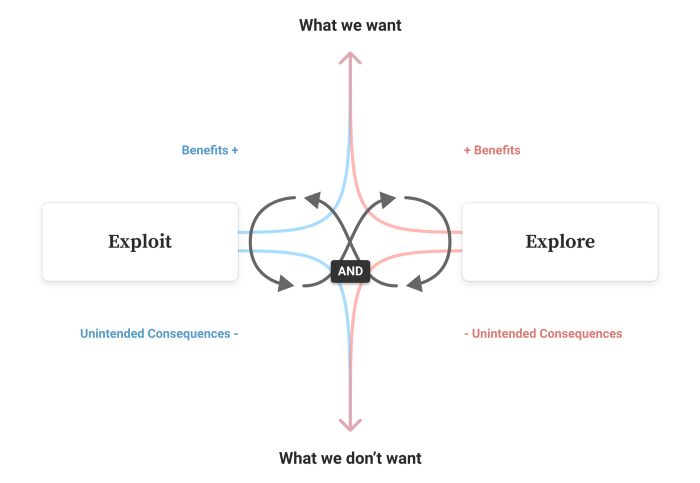

From this realization, we can add that the value of an innovation process is therefore not one of a production process, where outputs and quality are kings, but one of testing, learning and responding/adapting.

In business terms, we would call this an exploit-explore tension.

Complexity, Design, And Innovation: What The Matter?

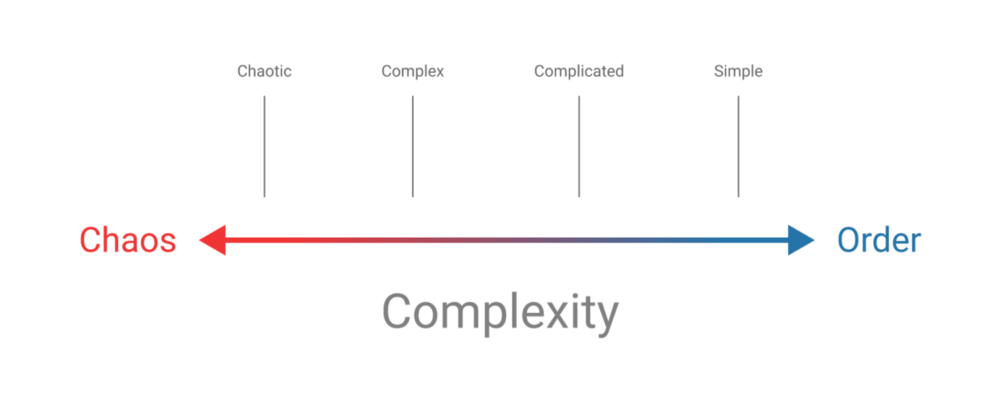

Change agents, have to face a harsh reality when they start to move into action: complexity [1][2][13][15]. It is the very state of the context the agents evolve in. As such, complexity is a relative notion: a gradient from chaos to order.

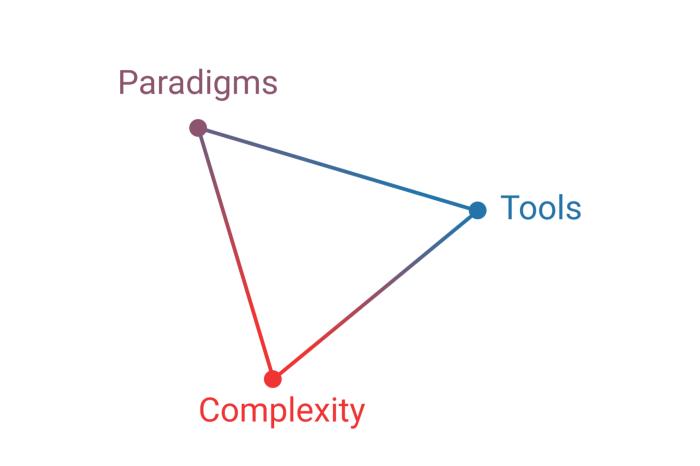

Interestingly, practitioners from various horizons have developed over time tools and paradigms to help them make sense and act within their environment. By looking at them from a complexity perspective, we can observe that some practices are better fitted for certain types of contexts: these are the different types of innovation (or design).

Complexity lies in every context.

This helps us understand the convergent and divergent aspects of the different paradigms and ideologies. We can now draw the interrelation between the complexity of a context (system), the tools, and the paradigms needed to tackle its challenges.

Deconstructing Paradigms: The Patterns Of Innovation

Interestingly, all these paradigms –and their tools (methods, processes, thinking styles)– display similar patterns with more or less degree: pattern identification, pattern optimization, and pattern creation.

Pattern Identification

Pattern identification is a key component, commonly found in most processes that aim to gain a (more or less) deep understanding of a problem/challenge and the situation in which it occurs. This is done by various means, some of which may involve field study (ethnography, user testing, etc.) or group exercises. I like to call it “mapping” –and a map can be more or less precise & detailed.

Pattern identification is literally the process of identification of relevant patterns (regarding the context) that have the potential to lead to “innovative” ideas — a meaningful change.

It is important to note that not all paradigms are equal in this regard and the methods used to achieve it certainly vary a lot depending on the paradigm that leads to the process. Neither they are always mindful of this very first phase the following thinking styles required to navigate an innovation process.

To quote Dave Snowden, the problem with paradigms is that “we don’t see what we don’t expect to see”.

Pattern Optimization

Pattern optimization [14] is the creation of value by modifying, improving, reshaping, or redirecting an existing answer to an identified challenge. This is mainly what “incremental innovation” does: perfecting the existing, the known, and maximizing its value.

Pattern Creation

Pattern creation [14] is the creation of value by diverging or departing from existing, typical, or conventional types of answers (solutions, ways of doing, etc.) to an identified challenge. This is exploring the unknown and thinking outside conventions of the said domain (i.e. industry).

What Are Paradigms?

Paradigms are pre-packaged, assumption-boxed, articulated answers to certain levels of complexity, build on different background history, assumptions, and ideologies. Through time, communities of practices created, borrowed, and re-appropriated tools, thinking styles, methods, processes, etc. to both make sense and address the complexity they were facing.

Lean, Design Thinking, Service Design, Human-Centered Design (HCD), Scrum, etc. are all paradigms. These paradigms include the different patterns (in some form) we talked about, as well as assumptions about what to expect from them.

For instance, a product thinking such as the Design Sprint or Agile assumes a certain type of results, which determines what to expect from the pattern identification.

Conclusion

Paradigms are useful constructions because they provide a simplified way to approach challenges through shortcuts, tools, thinking styles. But they rarely provide the necessary tools to identify when they become irrelevant or maladapted to our context — you know, because contexts are subject to changes.

“We don’t see what we don’t expect to see”

Most of the mismatch between our tools/paradigms and reality generally comes from our own ignorance and misplaced “faith”. It wouldn’t be so big of an issue if we could truly learn from this.

Learnings From Skepticism & Rationality

Paradigms deconstruction is a good first step in being aware of the preferences displayed (imposed?) by our paradigms.

Paradigms, like mental models, are subject to biases, assumptions, and call for motivated thinking, or as Julia Galef calls it, the Soldier Mindset metaphor.

Instead, she demonstrates what science showed to be the most effective thinking style to overcome biases, what she calls the Scout Mindset.

Toward Agnosticism?

Let’s face it, first, a project is rarely the best place to question our paradigms and we generally tend to follow the default ones at play in our organizations.

Secondly, paradigms are inevitable. Escaping our current ones to build a new, different understanding of the world is basically creating a new paradigm with its assumptions and tools — all models are a simplification of the world.

Besides, most often than not, paradigms are useful. What we must focus on is increasing our capacity to understand their limitations, and when one does not apply to what we’re facing.

Agnosticism is the art of saying “I don’t know AND I prefer not to believe”. Skepticism is the art of doubting and questioning our knowledge. The two are about building good practical epistemology and accepting the uncertainty of things.

If you are willing to explore beyond the boundaries of your own paradigms, join me and a growing community of thinkers & practitioners 👇

Sources, References, And Inspirations

a. Complexity & Systems Innovation

[1] Dave Snowden, 1999. Cynefin Framework, Wikipedia.

[2] Systems Innovation, an overview, 2018.

[3] Systems Innovation, Systems Change Book 2020.

[4] Systems Innovation, Systems Innovation Book 2020.

[5] Mikael Seppälä, 2020. “What are innovation ecosystems and what do they have to do with wicked problems?”, Sitra Lab.

[6] Simone Cicero & Al., 2020. Platforms-Ecosystems White Papers, The Platform Design Toolkit.

[7] Robert Rulli & Al., 2020. For Impact: Generate Snowballs, Don’t Select Snowflakes!, AXILO / Chôra Foundation.

b. Business & Innovation

[8] Alexander Osterwalder, Business Model Generation, 2010.

[9] Alexander Osterwalder, How To Build Invincible Companies, 2020 (book).

[10] Alexander Osterwalder, How To Build Invincible Companies, Strategyzer (Blog).

[11] W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, 2004. Blue Ocean Strategy, Harvard Business Review Press.

[12] Jan Spruijt, 2019. 4 Paths to a Sophisticated Innovation Strategy, OpenInnovation.eu.

c. Design & Innovation

[13] Systems Innovation, Systems Design Book 2020.

[14] GK VanPatter, 2018. Innovation Methods Mapping: De-mystifying 80+ Years of Innovation Process Design, Humantific.

[15] GK VanPatter, 2019. Rethinking Design Thinking: Making Sense of the Future That has Already Arrived (NextD Futures), Humantific.

[16] Gary S. Metcalf, 2014. Social Systems and Design, Springer.

Discussion